by Paul E. Nelson

Editor’s Note: Issue #68 of Rattle (Summer 2020) will feature a tribute to Postcard Poems. In the following essay, Paul Nelson describes his experience running the annual August Poetry Postcard Fest. It is our hope that more poets will participate this year and will save and submit their poems to our issue afterward, but participation in this festival is not required. If interested, though, the August Postcard Poetry Festival registration deadline is July 18th. For information on submitting to our postcard poems issue (deadline: January 15th), click here.

Photograph by Chad Peltola (CC0)

__________

We can write anything we want as long as we don’t show anybody.

—Allen Ginsberg

Spontaneous Composition

Every summer since 2007, hundreds of poets participate in an old school activity. They write poems onto postcards with a pen and send them to (mostly) strangers all over the world. They register for the August Poetry Postcard Fest, get a list populated with names and addresses and write those folks poems over the course of July and August. Some participants create their own cards. Some get cheap ones at the drug store. Some, like me, become postcard addicts, building their home stash year round and especially while traveling. By September 8th I usually have a stash of new poems that were composed for, and sent directly to, me. It’s a little intoxicating.

I started the August Poetry Postcard Fest in summer 2007 with Lana Ayers, who, with a great editor’s mind, put together some random notes I sent her and set the course of the project:

It is an experiment in composing in the moment and your poem has an audience of one. This is designed in part as a conversation … Write about something that relates to your sense of “place” however you interpret that, something about how you relate to the postcard image, what you see out the window, what you’re reading, a dream you had that morning, or an image from it, etc. Like “real” postcards, get to something of the “here and now” when you write. Present tense is preferred … Do write original poems for the project. Taking old poems and using them is not what we have in mind … This is also an experiment in community consciousness. Try to respond to cards that you get with subject, image, or any kind of link if possible. Often newsworthy events happen in August. How would our community respond? Letting a card that you receive linger for a while before you respond to the next person on your list is the preferred method. When you go to your mailbox each day, put the bills aside, read the poems you get and think about them as you compose to the next person on your list.

[perfectpullquote align=”left” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]This is also an experiment in community consciousness.[/perfectpullquote]My graduate work ended in 2007 and I was probably motivated by a zeal for spontaneous composition to create a project based on some of what I’d just taken in. I’d studied open form in North American poetry, focused on Walt Whitman, William Carlos Williams, Charles Olson, Denise Levertov, Robert Duncan, Michael McClure, and others from this stance toward poem-making. The letters of Levertov and Duncan were especially illuminating, as they called their method “Organic Poetry” and, despite the commodification of the word “organic” by the grocery industry, it resonated with me.

As the postcard fest got going, there were a few people who “got it” that the point was to begin to train yourself to discern the authenticity of immediate impulses and not worry about being judged, or writing the MOST BRILLIANT POEM EVER. David Sherwin wrote a piece that we link to each year in the official fest call entitled “How Sending Postcards to Strangers Made Me a Better Designer.” In it he said:

This sense of being grounded in the moment of composition, and writing words directly into the postcard with a permanent tool (pencil, pen, typewriter) can be a real struggle for anyone used to waiting for inspiration to strike. Modern writing tools, like the computer, may provide some help, but there’s too much risk that you’ll spend time editing and crafting the material instead of letting it happen in the moment of composition. If you write a word or phrase you don’t like, there’s no going back unless you scrap the postcard and start anew.

Needless to say, my first year of participation was a struggle. Breaking the rules, I wrote ideas in my notebook first, then copied the material onto postcards. While this satisfied my desire to make sure I liked what I’d written before I sent it off, I was totally missing the point: the project isn’t about writing great material …

I have a slight quarrel with that summation. It is about training yourself to be totally focused on the needs of the moment, on the needs of the poem, learning to trust that the language itself will say something through the poet. Duncan put it this way:

What do I do in a poem? … The only time my art comes forward is when I am actually attentive and immediately recognizing what those words are saying and bringing forward, and I work with them. I do not use language, I cooperate with language and that is a great distinction …

There are those who say the real work in poetry is in the editing. For them, it is. I would argue that it is because of their failure to yield to the language, or to their muse, or to the hard work of paying attention in the moment, or any number of reasons. Sure, in a batch of writing 31 poems within a time frame of 56 days, from the time the fest starts on July 4th to the end of August, there are going to be poems that are strong and those that are less authentic, or didactic, or clichéd, or abstract, or without any surprise moments, or lacking imagination, or any number of the usual reasons poems fail. Levertov argued that the reason extensive revision is needed in a poem is that it did not incubate long enough. I agree. The postcard fest does not leave much time for incubation, but participants can come to the fest with a variety of materials that can spawn ideas, much like Bernadette Mayer came to her legendary Midwinter Day project. How to write an epic poem in a day? How to elevate the everyday to the kind of material that would inspire an epic? There are lessons for every poet in Mayer’s project, but they seem especially relevant for postcarders.

The Fest

On July 4th each year, the festival begins as people who have registered get their lists. Last year there were nearly 300 participants. Once registered, as each list of 32 names fills up, that list is sent to everyone on the list, name and address in an order. If you are #4 on the list, you start writing original poems on postcards to the people below you on the list—number 5, 6, 7, and so on. If you are last on the list, you start at the top. As you get poems in the mail, hopefully there is an image, a tone, content, a topic, something that inspires you to write to the next person on your list. But the idea is that you compose the poem on the card, put a stamp on it, address it, scan the image and transcribe the poem for your records and head to the mailbox. I usually have an intention/prayer when I drop my latest postcard poem in the box. (Also a bit of sweet melancholy in letting the card go.) If you register on July 4th, get a list on July 5th, and start on July 6th, that gives you 56 days to write your 31 poems, hence the title of the postcard anthology 56 Days of August. Some people write more than 31. Some people create other postcard fests at other times of the year. Our fest’s Facebook group is quite active all year round but hopping when July 4th comes.

Discipline

Freedom in art, as in life, is the result of a discipline imposed by ourselves.

—Marianne Moore

One fest participant said that having the “soft deadline” helped in her fest participation. Yes, there are always those who are still sending cards in September, when I have written my annual afterword and am ready to go backpacking in Olympic National Park, but the fest affords the participants something of a discipline. Sit at your desk with maybe some potential epigraphs, having read the most recent poem or two that has landed in your mailbox alongside Safeway and Costco flyers and “This is Not a Bill” notices from your health insurance corporation and find the right card for the next person on your list. A groove begins eventually. The poem is only going to one person and perhaps a nosy mail carrier. I do remember a report of one postcarder who heard from their mailman about the quality of a postcard poem when they said: “Hey, this one’s pretty good!” By the end of August, if a participant practices as directed and does not try “cheating” they get a sense that they can learn to trust first impulses and look for what Jack Spicer called “the quick take.” Being afraid of failure hurts that process, as David Sherwin found out in his experience. Picking the right stamp can be part of the creative act too. But writing every day is like the golfer who practices every day and finds that he/she is “luckier” on the course when they practice more. Learning how to trust the first impulse, discerning quickly what is authentic, learning to focus on the “luminous details” as Ezra Pound would put it and you’re on your way.

Community

The fest is a return to old fashioned communication, postcards, and mailboxes. How quaint is that in our Facetime-across-the-ocean-instant-information world? Yet the Facebook page serves as support, as encouragement, sangha, and information post all in one. I suppose it is part of the irony that makes the fest unique, and I fought it for a while, actually turning off comments on the page during early fest seasons. But there is also something community-building in the process of sending cards to one another. With many of the poets originally coming from the networks Lana Ayers and I had in 2007, we’ll see postcarders at open mic events, readings, and elsewhere in the literary circles we travel. Sometimes we get to hear postcard poems at those events, which is sweet. But being the intimate act that correspondence is, the fest allows us to learn about people’s lives, become invested in them, and we are then allowed to be a little more vulnerable in our own writing and lives. As M. Scott Peck said, “There can be no vulnerability without risk; there can be no community without vulnerability; there can be no peace, and ultimately no life, without community.” This not only says a lot about the enduring appeal of the postcard fest, but how social media and the perceived anonymity leads to no vulnerability and less community.

Seriality

[perfectpullquote align=”right” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]… if you’re listening carefully to that voice, you follow your voice. You have to bow to your muse.[/perfectpullquote]Sometimes events happening during the postcard fest color the content. The wildfires affecting air quality last summer in Seattle were noted in several poems of mine and several I received in the mail. Last year I also deepened my practice of what Sam Hamill called “The sequential poem” and what is also known as the serial poem. I would use a line or image near the end of one poem to start the next. This a technique put to good use in Michael McClure’s long poem “Dolphin Skull.” Hamill used it later in his poem “Habitations” and told me in 2010:

The poem in sequence can be inspired in various ways. One of them is simply through lyrical form, which provides a kind of syntax which one begins to follow. One returns to that music, that language with a certain ability to listen within yourself and extend rhythm, extend that kind of speech. Extend the meditation, but not in a narrative way which is necessary for the epic. The epic has to have a narrative base, and while there may be narrative impulses and shadows in the serial poem or the sequential poem its root is not a narrative poem. Its root is shorter and more lyrical.

Hamill agreed that if there’s a narrative thread to the poem in sequence, it’s often one that develops organically and outside the awareness of the poet writing. He also said:

Sometimes you write something and you think, you know, “I got it.” And then you come back to it a week later and you realize, “Well, this isn’t really the end. This is a pause. But I have more to say in this way and in this style and in this voice,” and if you’re listening carefully to that voice, you follow your voice. You have to bow to your muse.

Sure, any two postcard poems are usually going to two different people, but they serve to deepen the poet’s experience in the act of composition. Somehow I think each receiver of the different postcards can sense the energy.

In an interview I did with Cuban poet José Kozer, he also discussed seriality:

I think that my concept of a poem is incompleteness. The poem itself, when it’s finished, no matter how successful or unsuccessful it is to me, it is never a completed poem. A poem is always open, even though it’s closed at the end, to continuity. It’s, for me, a strategy easy to pursue to take a point in a poem that I’ve already written, even publish it and departing from that moment in that poem, write another poem so that they are linked, they are, series-wise, they are somewhat formulated a priori. They exist unto themselves. There’s nothing to be forced as to its continuity. It dies out because, technically at one point, you’ve said so much and you cannot give anymore to that series, but it doesn’t mean that the series is dead.

In an interview I did with Nate Mackey, on seriality he said something similar to Kozer, that seriality allows:

The possibility of things coming into the poem that were not necessarily resolved … not necessarily pursued to their fullest or most exhaustive sense … things to come into the poem that … have a life beyond that particular poem and … become part of an exploration … the serial poem allows that.

One also thinks of Monet’s haystacks or his Rouen Cathedral series to know that artists other than poets have strived to get at something and learned it often requires more than one pass at the subject. The legendary Gemini G.E.L. Gallery had a whole exhibit dedicated to seriality that was presented at The National Gallery in Washington, D.C., and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and featured the serial work of Jasper Johns, Roy Lichtenstein, Robert Rauschenberg, Frank Stella, Baldessari, Julie Mehretu, Richard Serra, Tacita Dean, Analia Saban and others.

Just the act of writing so many poems similar in length, in form (epistolatory), and in a short amount of time lends itself to seriality.

Visual

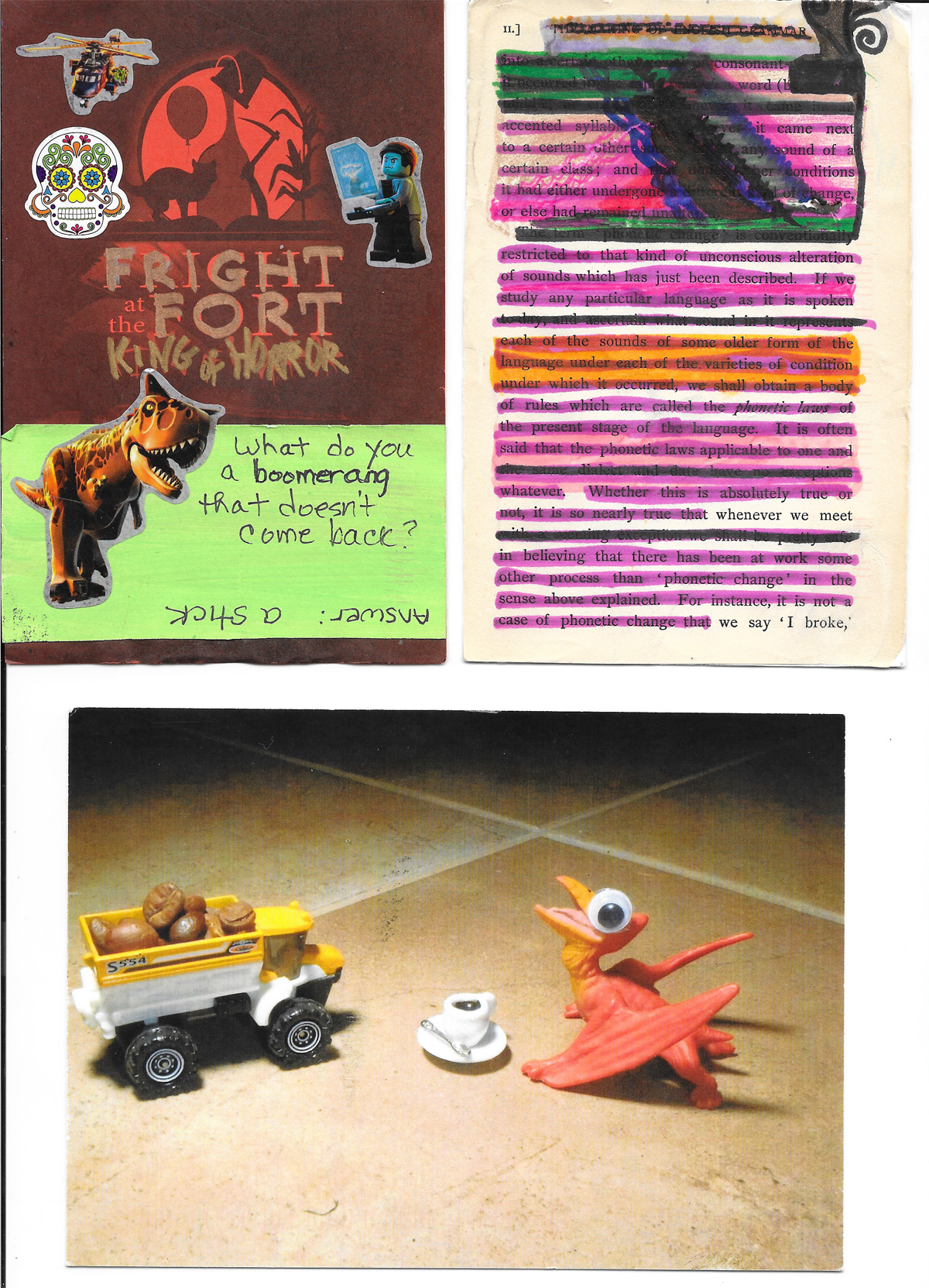

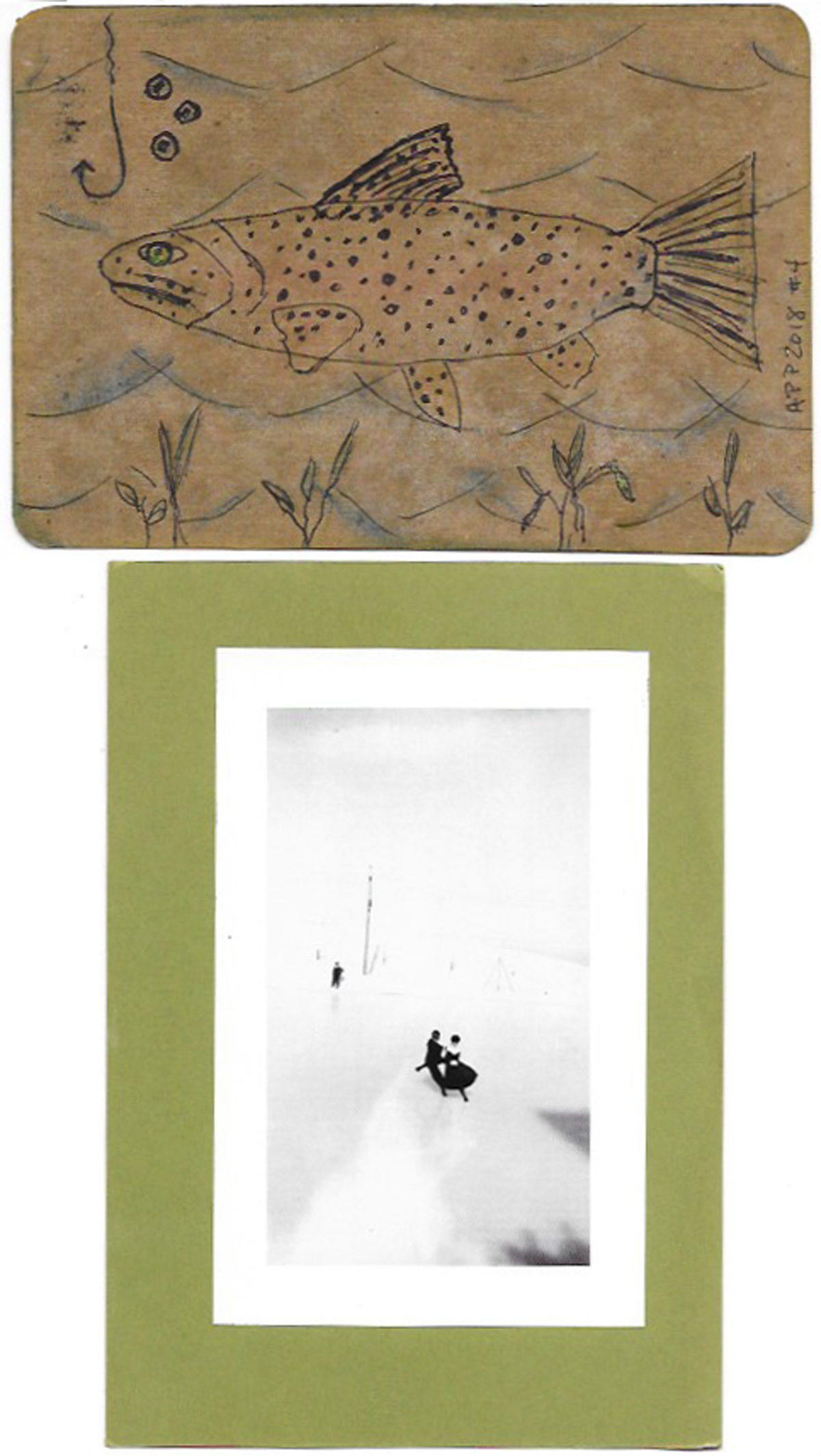

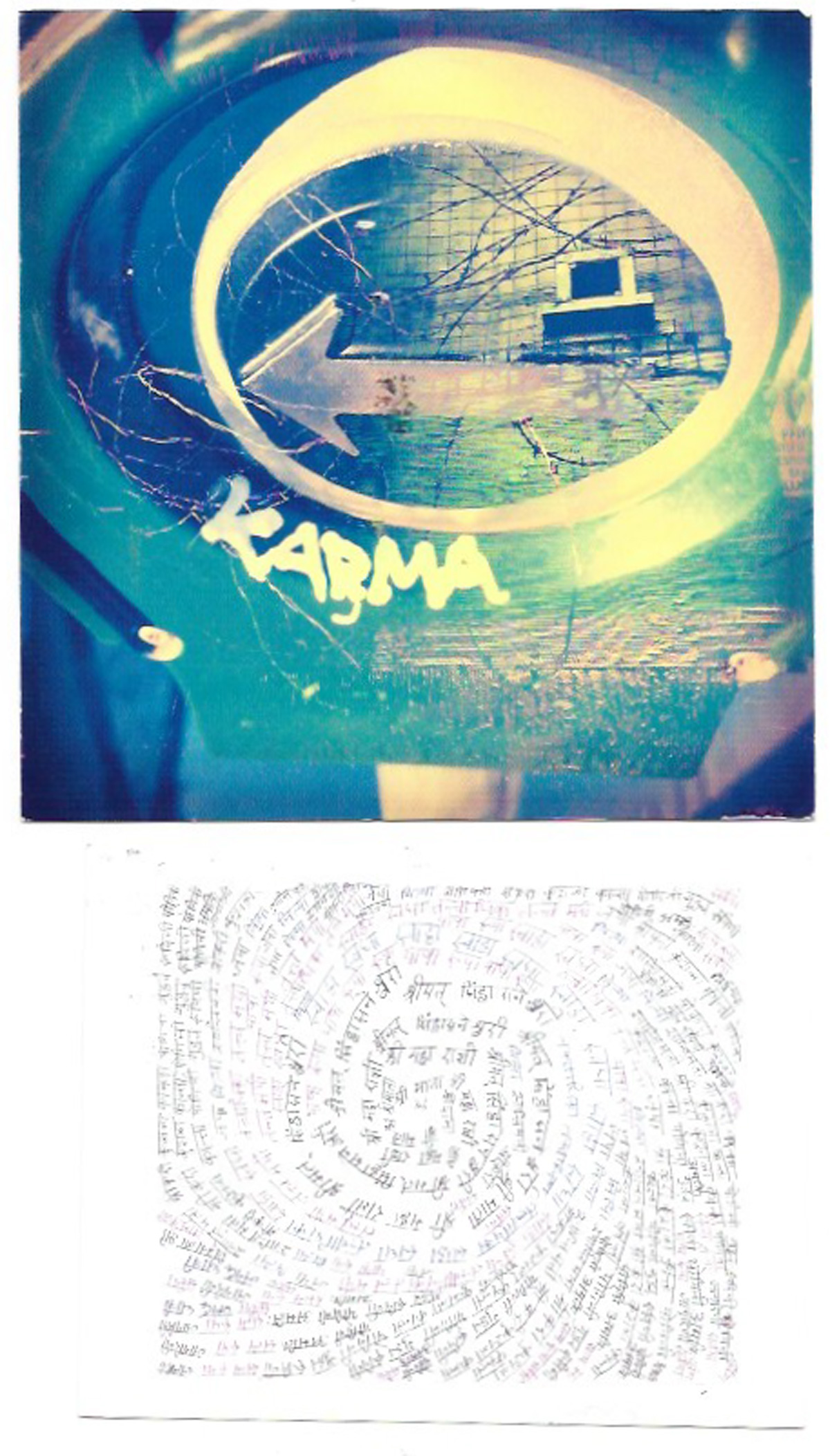

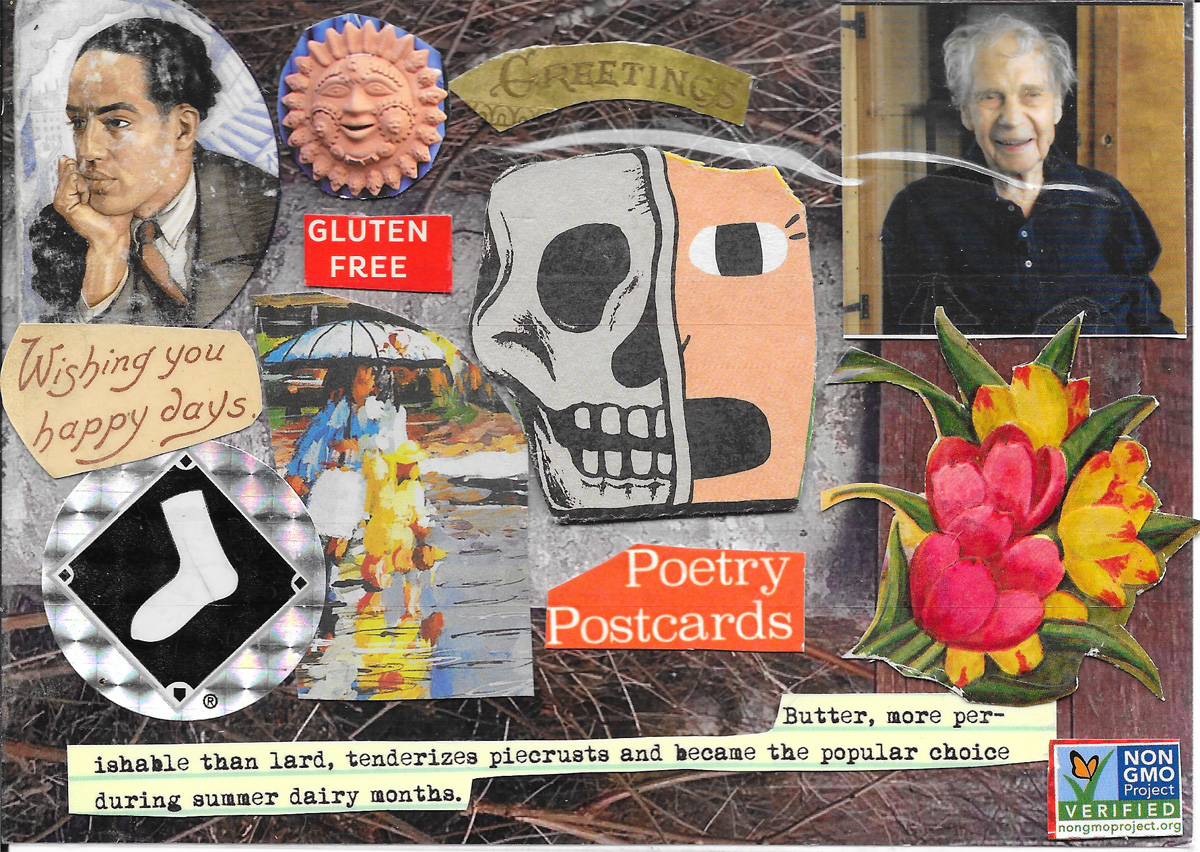

In the past few years the creative frontier of the fest has moved to the front side of the cards, in the actual images that people create themselves. Here are a few examples of some of the homemade cards I received in 2018:

Top left: Sigrid Saradunn, Ellsworth, ME; top right: Hannah Craig, Pittsburgh, PA; bottom: Rich Maschner, Corona, CA.

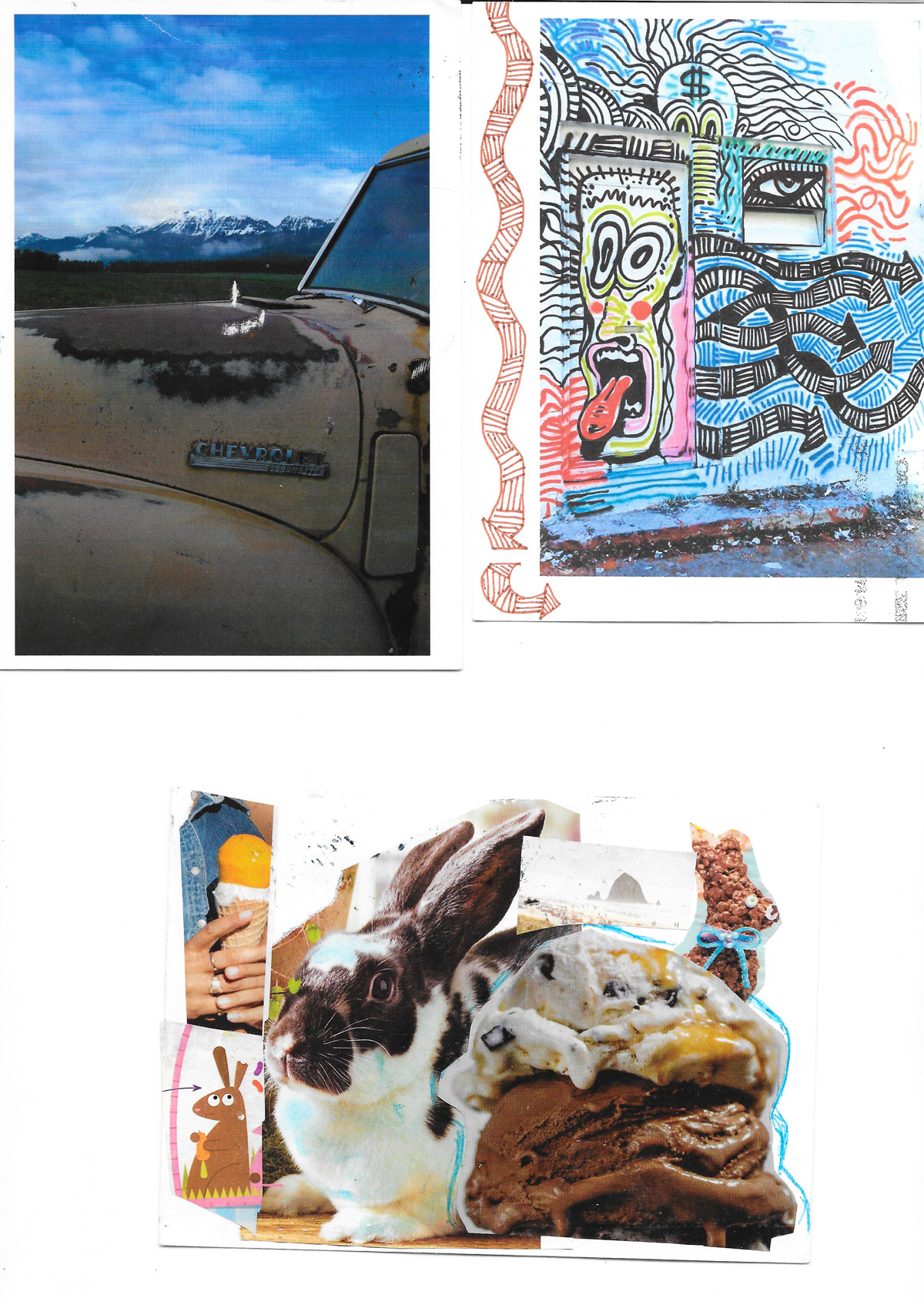

Top left: unsigned, Portland, OR; top right: Peggy Miller, Orlando, FL; bottom: Danita Smead, Sedro Woolley, WA.

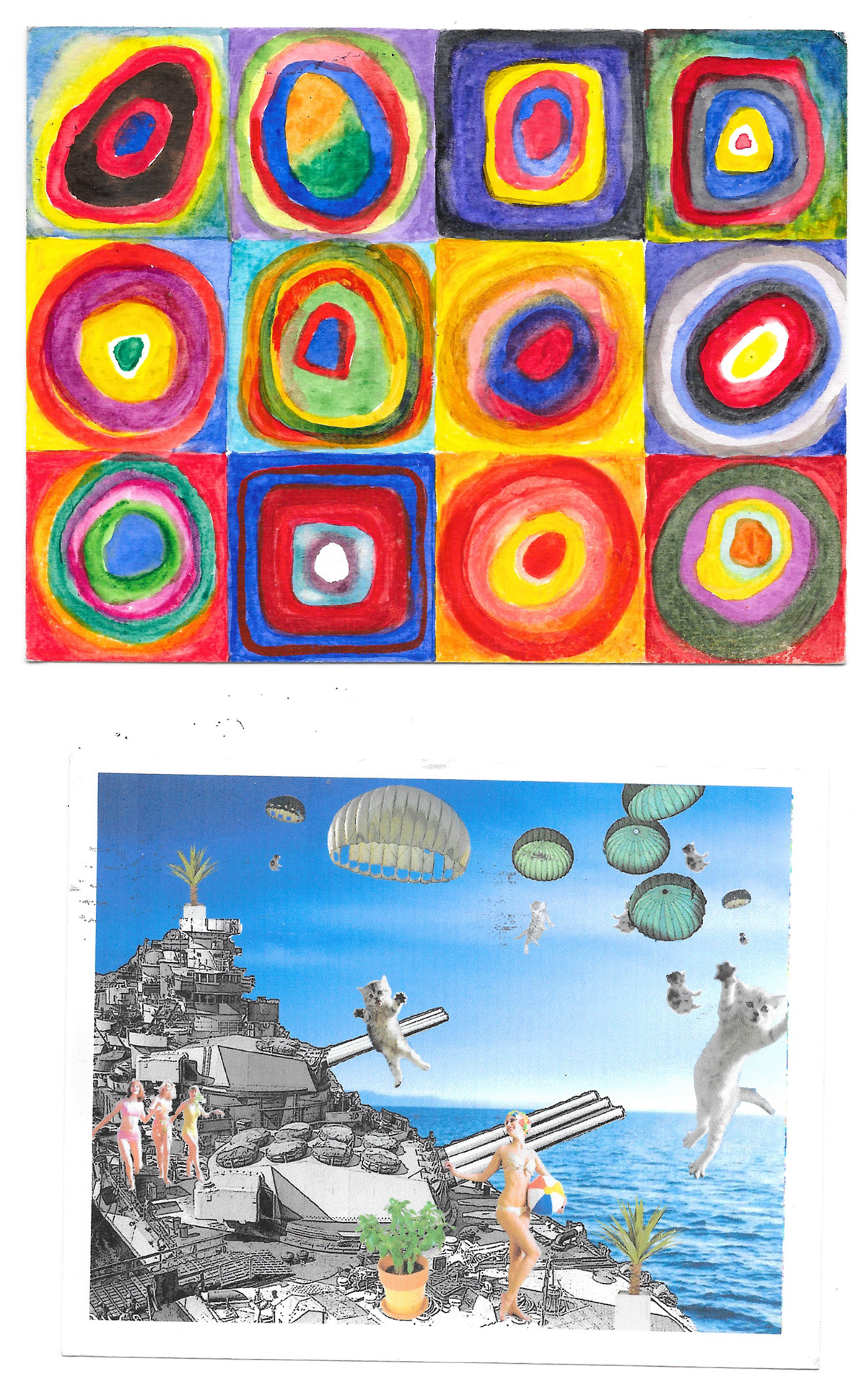

Top: Abhaya Thomas, Portland, OR; Brendan McBreen, Pacific, WA.

Carolyn McCarthy, Bow, WA.

Top: Colette Dutton, Federal Way, WA; bottom: Sarah Koenig, Seattle, WA.

Top: Matt Trease, Seattle, WA; bottom: Stanley Del Gozo, Deming, NM.

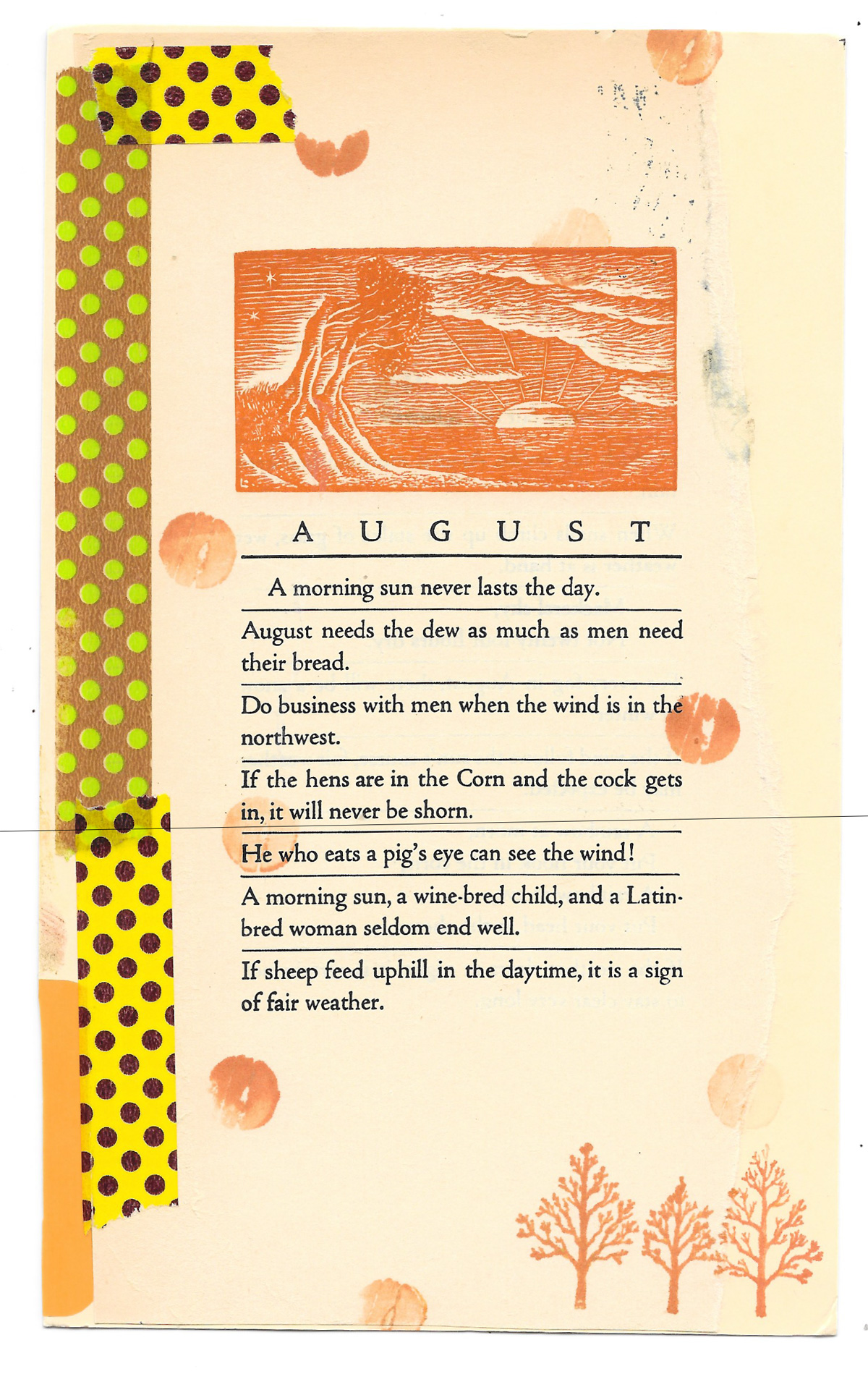

This last one (above) is my image. During the 2018 fest I started getting more interested in creating my own collages. I had sent many postcards in previous years with my own photographs on the front of the card, but this was a new twist to the fest for my own participation.

When July 4th comes around, I have a rush of signups and then the next week is slower for registration, but once it closes, the fest starts again for me. It would not be “August” without the August Poetry Postcard Fest. I have heard this from long-time participants, that it feels like its own time of year, like the holidays. In the last couple of years this has become the largest annual fundraiser for SPLAB, the Seattle Poetics LAB, and that it is an exercise in spontaneous composition and self-guided openness are elements of the life of a poet we like to support.

__________

Paul E. Nelson founded SPLAB (Seattle Poetics LAB) and the Cascadia Poetry Festival. Since 1993, SPLAB has produced hundreds of poetry events and 600 hours of interview programming with legendary poets and whole systems activists, including Allen Ginsberg, Michael McClure, Joanne Kyger, Robin Blaser, Diane di Prima, Daphne Marlatt, Nate Mackey, George Bowering, Barry McKinnon, José Kozer, Brenda Hillman, and many others. Paul’s books include American Prophets (Interviews 1994-2012) (2018) American Sentences (2015), A Time Before Slaughter (2009), and Organic in Cascadia: A Sequence of Energies (2013). Co-Editor of Make It True: Poetry From Cascadia (2015), 56 Days of August: Poetry Postcards (2017), Samthology: A Tribute to Sam Hamill (2019), Make it True meets Medusario (2019), he’s presented poetry/poetics in London, Brussels, Nanaimo, Qinghai, and Beijing, China, has had work translated into Spanish, Chinese, and Portuguese, and writes an American Sentence every day. (web)